White Spruce (Picea glauca)

White Spruce trees are one of the most widespread conifer trees in Alberta’s boreal forest. They grow in well-drained, moist soils and can be found throughout western, central, and northern Alberta. This evergreen tree is a common winter food source for many birds and mammals - especially squirrels, who rely on their cones as a primary food source!

White Spruce trees also have a variety of uses for people. The branches have been used to make lean-to shelters and wind barriers, and larger wood pieces, once dried, act as good canoe frames, paddles, and snowshoes! The needles or tips are stiff and have a bright green colour, and add a citrusy flavor to salt and sugar.

Before foraging for the required ingredients, we recommend taking a look at our Sustainable Foraging Guide!

Culture Connection

Nehiyawewin (Cree):ᓯᐦᑕ Sihta

When Jacques Cartier and his men first landed in Canada they were plagued with scurvy, a vitamin c deficiency. They landed in Quebec in the territory of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), during the winter. The Haudenosaunee treated the men by giving them tea made from the bark and needles of a conifer, likely a white spruce tree.

But the high vitamin C content isn’t the only benefit that spruce needles are known for. The Nlaka'pamux (formerly called Thompson) of southern B.C. used a mixture of spruce needles and resin as a cancer treatment. The Anishnaabe (Ojibway) used dried spruce needles to disinfect the air. Other parts of the spruce tree were used including the roots, inner bark and resin. Many different nations used the pitch of spruce trees as a dermatological aid for cuts, burns, rashes, sores, dry skin including the Nîhithaw and Nehiyawak (Woodlands and Plains Cree people), many Inuuk (Inuit cultures) and the Xa’islak’ala (Haisla). Spruce resin was used by many different nations across Canada and the U.S. as chewing gum.

Collect your spruce tips in the spring when the brown sheaths that cover the new tips are still loosely attached to the end. White spruce trees are ideal, but black spruce or pine can also be used.

Ingredients

Spruce tips

White sea salt or kosher salt

Method

Use a 1:1 ratio of spruce tips and salt.

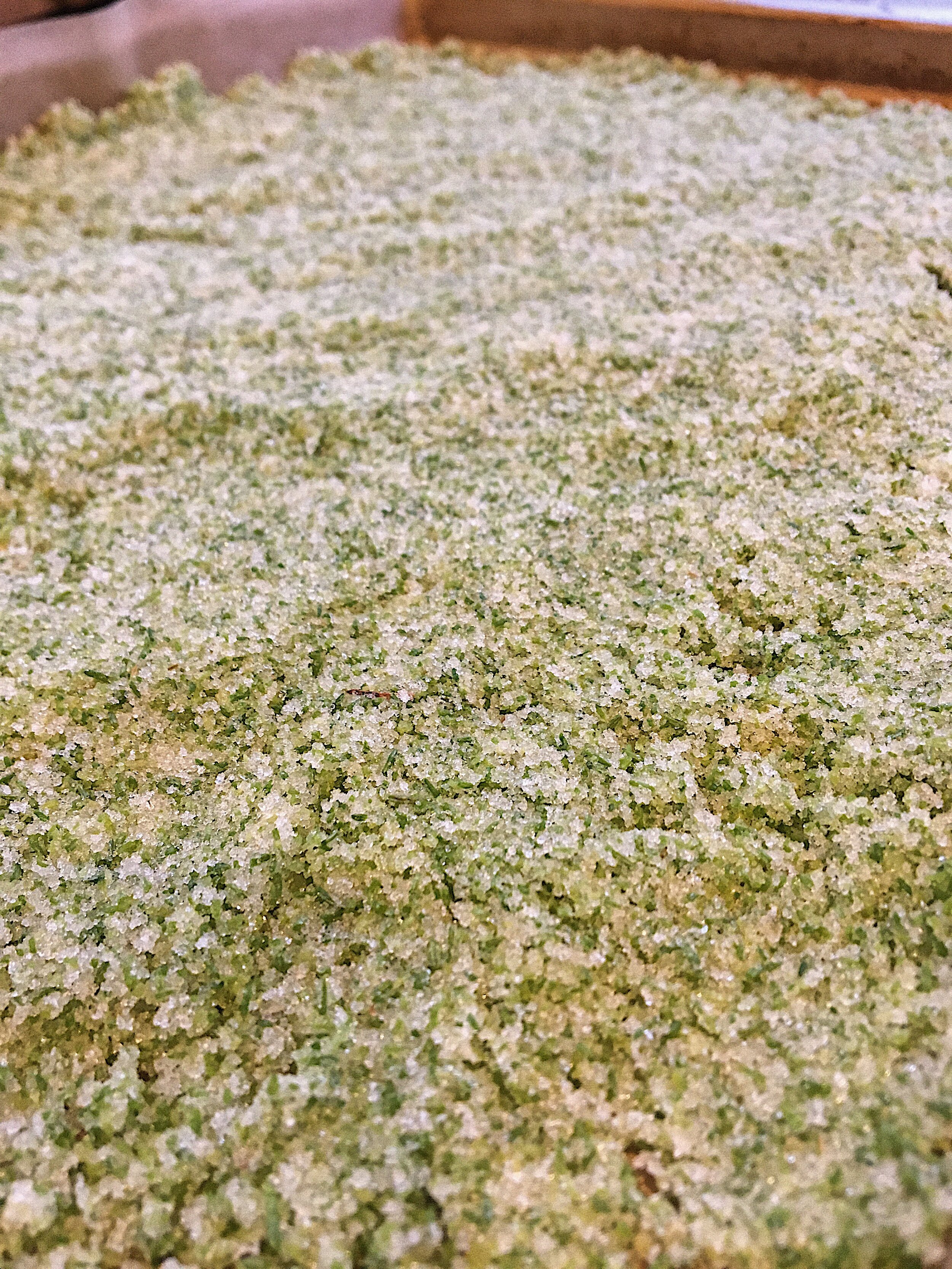

Rinse and clean the spruce tips of any remaining bracts or debris and food process until fine. Add the salt and food process again until combined.

Spread the salt mixture evenly on a tray lined with wax paper and leave until dry - this may take several days.

Store in your pantry and add to fish, eggs, vegetables, or anywhere else you’d like a natural, lemony flavour.

Tip: Try making spruce tip sugar in the same way by starting with a ratio of 1:2 tips to sugar. Use this for the spruce tip shortbread recipe!