The Edmonton area is rich with history of diverse Indigenous Peoples. We wish to acknowledge the history of all Indigenous Peoples within the Edmonton area and share some knowledge about the history and importance of our region and the regions in which our conservation lands are located.

Treaty 6

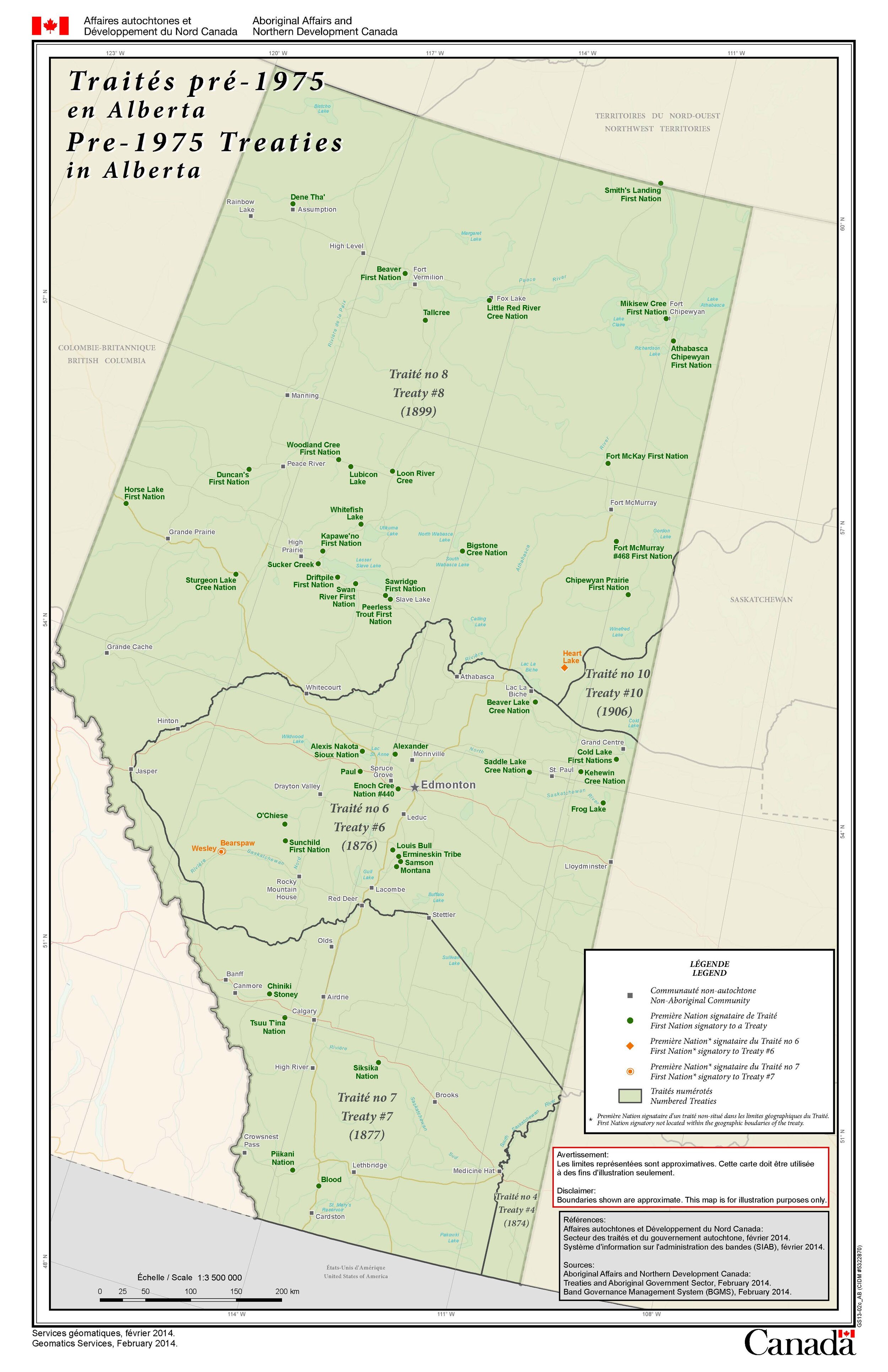

Edmonton lies in Treaty 6 territory, a traditional gathering place, travelling route and home for many Indigenous Peoples including the Nehiyawak/Cree, Tsuut'ina, Niitsitapi/Blackfoot, Métis, Nakota Sioux, Haudenosaunee/Iroquois, Dene Suliné, Anishinaabe/Ojibway/Saulteaux, and the Inuk/Inuit. Treaty 6 was first signed in 1876 at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt in Saskatchewan between the Nehiyawak, Dene Suliné, Nakota Sioux, and the Crown. Later on, many other Nations signed adhesions to the treaty in order to provide for their communities. Today Treaty 6 encompasses 17 First Nations. Given the language/ cultural divide and differing motives the Treaties are surrounded with many misconceptions, particularly between the conceptions of sharing the land and land cessation. Treaty 6 recognition day is every August 23rd. It was initiated by The City of Edmonton to commemorate the signing of Treaty 6 at Fort Carlton on August 23rd, 1876.

ᐊᒥᐢᑲᐧᒋᕀ

amiskwaciy

Amiskwaciy means Beaver Hills in Nehiyawewin (Cree). The name for Edmonton, amiskwaciy-wâskahikan, means Beaver Hill House. The Niitsitapi and Nakota words for the region are kaghik-stak-etomo and chaba hei, respectively. The Niisitapi called Beaver Hills Lake kaghikstakisway, which means “the place where the beaver cuts wood”. Historically, the Beaver Hills region was important for the Tsuut’ina (Sarcee), Nehiyawak (Cree), Anishnaabe (Saulteaux), the Nakota Sioux, and the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot). The region’s dense forests, open plains, and lakes offered many resources for different Nations to rest and replenish their stores through hunting, gathering and fishing. The abundance of rich resources in the region made it an important place to rest during long voyages between the hills and the prairies, which happened each spring and fall. Activity in the region dates back to over 8,000 years ago. 200 Indigenous campsites and tool making sites have been found by archaeologists within the region.

ᑭᓯᐢᑲᒋᐊᐧᓂᓯᐱᕀ

kisiskâciwanisîpiy

Kisiskâciwanisîpiy is the Nehiyawewin (Cree) word for the North Saskatchewan River, it means swift flowing river. The name Saskatchewan, for both the river and the province, is derived from the Nehiyawewin name. Larch, Pipestone Creek, Coates and Visser all lie along the river valley of the North Saskatchewan. The river and river valley were traditionally important for many nations including the Nehiyawak (Cree), Tsuut’ina, Anishnaabe (Ojibway/Saulteaux), the Nakota Sioux, the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the Métis. The river valley was historically important for harvesting food and medicine, fishing, and harvesting materials for tool crafting. Chert and quartisite are present in the river valley. They are easily knapped into various tools such as axes, knives, and projectile points. Evidence of Indigenous Peoples living around the North Saskatchewan River spans back to over a thousand decades ago. The North Saskatchewan and its tributaries were the main modes of transportation for thousands of years. The river leads all the way to Lake Winnipeg and the Hudson’s bay region. The voyage from the Edmonton region to the Hudson’s bay region has been made many times over, particularly during the fur trade.

Photo by Norm Legault

ᒪᐢᑭᐦᑮ ᐱᒣᐢᑲᓇᐤ

maskihkîy meskanaw

The area surrounding maskihkîy meskanaw/Glory Hills Conservation Lands has ties to the cultures of both the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and the Nêhiyawak (Cree).

The hamlet of Calahoo lies northeast of maskihkîy meskanaw, and is named after the family and starting members of the Michel First Nation. The Michel First Nation took the namesake of their first Chief, Michel Caliheue, who was son of Louis Caliheue, known as “The Sun Traveller”. Louis Caliheue was a Mohawk man from Kahnawake, Quebec. He originally worked for the Northwest Company in the fur trade as a canoe man and, later on, as a steersman. After his contract was up, Louis Caliheue became a “freeman” and could freely trap and trade furs to whoever he wished. Many free men came to the Edmonton area. Soon enough, a community of locals and freemen with both Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Nehiyawak (Cree) descent began to form.

Further northeast lies the Hamlet Rivière Qui Barre, which is a French translation of the Nehiyawewin (Cree) name Keepootakawa, meaning river which bars the way. This is in reference to a nearby shallow river. During the time of the early logging industry, logs were brought down rivers from forests to saw and pulp mills. Unfortunately, this river was too shallow to allow logs to pass.

Bunchberry

Connecting Bunchberry to Edmonton is Maskêkosihk Trail ᒪᐢᑫᑯᓯᐦᐠ ᐟrᐊᐃl . Maskêkosihk Trail was named in a partnership with Enoch Cree Nation and the City of Edmonton. It means “people of the land of medicine” in Nehiyawewin (Cree). This project helps to promote both Nehiyawiwin and Nehiyawewin (Cree culture and language). Maskêkosihk Trail also connects Edmonton to Yekau Lake and the Enoch Cree Nation Cultural Grounds, where Pow Wows were once held.

Pipestone Creek

The waters of Pipestone Creek curve and bend into an interesting story. Pipestone Creek is a tributary of the Battle River, a name most likely inspired by the rivalry between the Iron Confederacy (Nehiyaw-Pwat) and the Black Foot Confederacy (Niitsitapi). The creek itself lies within Wetaskiwin County. Wetaskiwin is Nehiyawewin (Cree) for The hills where peace was made. This name comes from the story of an unlikely friendship between two rival chiefs; the Cree chief Little Bear, and the Black Foot chief Buffalo Child.

Downstream of Pipestone Creek is Meeting Creek. Oral history tells us this area is named Meeting Creek because it was a traditional meeting place between the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the Nêhiyawak (Cree), where they would meet to trade, and hunt along Battle River.

Coates Conservation Lands

The region around Coates, including Pigeon Lake to the south, was home to the Samson Cree, the Montana Cree, the Louis Bull Cree, and the Ermineskin Cree nations who eventually formed the Pigeon Lake First Nation. There are a number of sites inspired by Nêhiyawîhcikêwin (Cree culture) within the region.

The summer village of Itaska lies on the Northwest edge of Pigeon Lake. The village’s name comes from the Nehiyawewin word ispâskweyâw, meaning High trees on the edge of wood, referring to the beautiful forest bordering the edge of the water.

Another village inspired by Nêhiyawîhcikêwin is the summer village of Sundance beach. The Sun Dance is a sacred ceremony practiced by Indigenous cultures in Canada and the United States. Many laws have been placed in an effort to destroy the tradition of the Sun Dance. It was only in the 1950s when Indigenous citizens of Canada were once again allowed to openly practice the Sun Dance, but social circumstances still made people feel unsafe in practicing the Sun Dance for a while afterward. Before taking part in the ceremony one must fast from food and water. The ceremony itself is meant to be a physical and spiritual test in which one partakes as an offering to their community.

Last but not least is Ma-Me-O Beach, which was part of the Pigeon Lake First Nation until it was obtained and developed in 1924 to later become a Provincial Park. The name of the beach is derived from the Nehiyawewin (Cree) words for white pigeon. The names of Ma-Me-O Beach and Pigeon Lake are most likely inspired by the large flocks of passenger pigeons that once inhabited the area.

Passenger pigeons were a great source of food for Europeans and Indigenous people alike. The Onöndowága (Seneca people), a Nation living south of Ontario lake, called the passenger pigeon jahgowa, which means big bread, since it was such a critical source of nourishment. Enormous flocks of passenger pigeons instilled fear, wonder and excitement into observers. One personal account from the 1800’s recalls a flock so great that it took over three days to pass.

Photo by Norm Legault

Lu Carbyn Nature Sanctuary

Lu Carbyn Nature Sanctuary is located within a picturesque landscape dotted with lakes and wetlands. The largest water body within the region is Wabamun Lake. Wabamun is derived from the Nehiyawewin (Cree) word for wâpamon, which means mirror, in reference to the stunning reflective waters. The second largest water body within the region is Lac Ste. Anne. Lac Ste. Anne has also been called Wakamne, meaning The Creator’s lake, by the Nakota (Assinoboine). The Nehiyawak (Cree) called the lake Manitou Sakhahigan which translates to Lake of the spirit. The lake was said to have healing powers and was visited by many nations, including the Nehiyawak and the Nakota, before the arrival of Europeans. There are stories of Nakota ancestors who heard singing from the lake and understood it as a message from The Creator telling of the lake’s healing properties.

Today Lac Ste. Anne is visited by people of many different walks of life, including those on an annual Catholic pilgrimage held each July. Due to the significance of the pilgrimage and its long-standing tradition of over one hundred years, Lac Ste Anne has been named a National Historic Site of Canada. To learn more about the pilgrimage follow this link.

ᒥᓂᐢᑎᐠ

Ministik Conservation Lands

Ministik ᒥᓂᐢᑎᐠ means “island” in Nehiyawewin (Cree). This name is most likely in reference to the many small islands within Ministik Lake. Ministik borders the federal riding of Crowfoot. Crowfoot (Isapo-Muxika) was a Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) Chief of the Siksiká First Nation. Crowfoot was very well respected within the Niitsitapi Nation. He also aided in fostering peace between the Nehiyawak (Cree Nation) and the Niitsitapi after raising a nêhiyâsis (Cree boy) who later became a great leader with a possibly complicated but still strong relationship with his adopted father. Originally after Crowfoot’s son had been killed during a battle with the Nehiyawak, he sought vengeance and led a raid against them with the sole purpose of killing one Nehiyaw, when the young teen they had captured bore a resemblance to his late son he opted to adopt him instead. This teen later became the Nêhiyaw Chief known as Poundmaker (Pîhtokahanapiwiyin), who was active in the North West Rebellion.

Golden Ranches, Hicks, Smith Blackburn Homestead

Golden Ranches, Hicks and the Smith Blackburn Homestead are near Cooking Lake and within the Beaverhill Biosphere Reserve. Cooking Lake is an English translation of the Nehiyawewein (Cree) word opi-mi-now-wa-sioo which means cooking place. The lake was a well frequented Nehiyaw (Cree) campground due to the large herds of bison that once roamed the area. Bison are very important to plains cultures, as they were the main source of food and provided hides for clothing and shelter. Other body parts of the bison, such as hooves, bones and sinew were used for tableware, knives, toys, and bow strings. For the Nehiyawak (Cree), the Buffalo is the Chief spirit of the four-legged creatures.

Just north of Golden Ranches is Elk Island National Park, which has helped to preserve a disease-free bison population. Elk Island has also relocated bison to traditional territories in three different nations including The Blackfeet Nation in Montana and The Saulteaux and Flying dust First Nations of Saskatchewan.

Sources:

Parks Canada - Lac St. Anne Pilgrimage National Historic Site

Dempsey, Hugh A. (1972). Crowfoot: Chief of the Blackfeet. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 71 & 72.

Three Hundred Prairie Years: Henry Kelsey's "Inland Country of Good Report"

Consultation with Elders